There’s a few factors that have been strongly contributing to Africa’s economic, humanitarian, and self-sustaining growth in the last couple decades. For example, the governments of a number of countries are becoming more democratic and reliable in terms of how much trust the citizens of each nation have in their leaders (These nations including Ghana, Botswana, Mozambique, Cape Verde, and a cluster of others). Another couple examples are the inundation of more reasonable economic policies, thanks largely in part to Nelson Mandela in the ’90s ending apartheid and uniting South Africa, which helped a number of businesses build the trust required to expand and help fuel domestic growth, as well as the large subtraction of debt from many of these nations. With fewer countries owing money to each other, tensions were lowered and they were excited to build a future together without the burden of wondering whether or not potential allies would be a mistake to invest in. In the wake of a technological revolution, you could find a cell phone in the hands of most citizens of these emerging countries as well, and with that comes even more opportunity for growth. They give healthcare workers a chance to spread important news of potential outbreaks or studies in different areas. The new technology has opened up the doors for jobs as coders and data entry careers, and it removed barriers for those located in different parts of the country or continent. People can now get to know and understand each other with fewer preconceived notions of places that they previously didn’t associate with (not in all cases but some) (Emerging Africa: how 17 countries are leading the way).

Plenty of countries are coming out from under the weight of poverty and helping their inhabitants the chance to live life without fear of hunger or safety, and it’s really exciting to learn about. Some countries on the other hand don’t have that same luxury as of late. My chosen country to research, South Sudan, is not in the same boat as these prospering lands.

South Sudan, as most are aware, has been in the throws of civil war and rebellion for the last five years or so, beginning with, as I’ve read/watched, the secession of themselves from Sudan, the now separate entity. In the search for freedom of religion and one’s own belief, new tensions quickly arose between the president and VP of the newly established country, when the president accused the VP of a sort of treason. President Kiir being a member of one tribe and Vice President Machar being of another, this rapidly promoted a sense of hostility between tribes. This resulted in a rebel uprising in the newly developed society and has since sent them down the path of civil war, which they broke away from Sudan to eradicate for themselves in the first place (Why is there conflict in South Sudan? | Let’s Talk | NPR).

In the time since civil war in 2013, over 400,000 South Sudanese citizens have been killed, over 4 million have fled the country, and plenty within the country have been displaced. Now as tensions have lowered a bit, President Kiir and former Veep Machar have signed a treaty uniting the two militaries as one, but a lack of funding has kept them from moving forward. As a result, the lack of finalization of their plans to come together has kept the country from developing further. They still rely heavily on aid, but with the constant expansion of deadlines is making countries like the U.S. hesitant to continue giving relief if the light at the end of the tunnel is still not in sight (South Sudan: A Last Chance for Peace? DW News).

As it goes, the factors that were helping nations like Ghana and Mozambique prosper are nowhere to be found in South Sudan. After all the fighting that it took for them to secede in the first place, then further violence in their newly established home, there’s still little trust to be had in their government, technology can’t be afforded by those who don’t even have access to a reliable food source, and the country hasn’t yet figured out an economic plan that unites the people when they can’t come to guaranteed peace in the first place.

It’s entirely possible to be trapped in poverty. Trapped doesn’t have to imply permanence, but it does promote fear of permanence. There are hundreds of countries around the world that have been stuck in a state of instability for decades, or centuries in some cases (Poor economics: barefoot hedge-fund managers, Diy doctors and the surprising truth about life on $1 a day). But, as previously stated, it’s possible to come out of. With some well-placed help and under the right circumstances, countries can be pulled out of debt. In the cases of Botswana and Ghana, it starts with democracy. South Sudan has elected officials, but they don’t have trust for them to end the fight they continue to have with themselves over topics as simple as “This is where I harvest!” “No! This is where my cows graze!” Tribalism, as it stands, is still an issue that promotes violence against other tribes (not unlike patriotism). And within the governed vs. the rebels, the land of rebels is being left out of government-run health and food programs, which only escalates tensions.

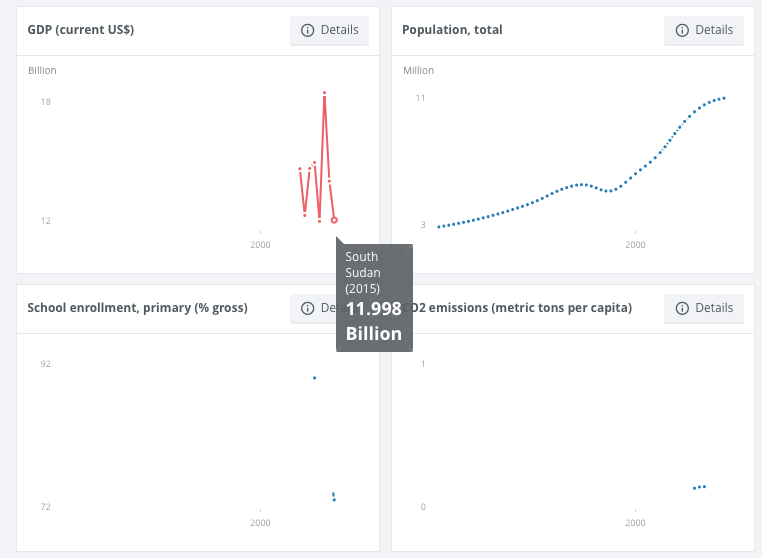

The World Bank website offers some questionable information on South Sudan. It claims that the population of the country has only gone up since 1994 until 2018, where it stops. This doesn’t fall in line with the numbers reported previously regarding all the deaths and and the 4 million emmigrants of the country. The charts regarding CO2 emissions, school enrollment, GNI per capita, and GDP haven’t been updated since 2015, which isn’t a good sign. And the life expectancy has only risen since 1960, which doesn’t seem to add up either, given the famine. I also assume that the stats about the country before the country’s founding in 2011 just speaks of the area before it became its own unit. The Gross Domestic Product dropped critically after 2013 when rebellion began to take place and hasn’t been reported to come up since, at least according to World Bank. This goes to show that the Sustainable Development Goals aren’t being met even a little bit since the country is no longer in a state of war, but is still more or less war-torn. Poverty headcount increased by nearly 18% between 2016 and 2018. But thankfully CO2 emissions only rose by .01% in the last year that they collected data. (Year in Review: 2017 in 12 Charts), (https://data.worldbank.org/country/south-sudan).

It’s hard to report that there’s no capacity for human capital in South Sudan (Human Capital definition and importance), but the statistics look bleak. To assume that the citizens of the country aren’t fit to work based on their lack of formal education and creativity given their current situation. There’s not a lot of job security in a land with no security at all, so it human capital in the nation looks almost nonexistent on paper. South Sudan’s is also not taken into account on many lists outside that of the world bank. I assume this is due to the lack of organization necessary to collect such data accurately. But I suppose my question is: Can human capital be calculated by stats such as these? In a country that doesn’t hold opportunity for capital, does that mean that the people aren’t capable of it? Or is it that its leaders have to organize themselves before the people are able to help the nation capitalize? And is it unethical for organizations like the IMF to pay no mind nations locked in poverty like this?

Year in Review: 2017 in 12 Charts. (n.d.). Retrieved February 3, 2020, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2017/12/15/year-in-review-2017-in-12-charts

Pettinger, T., Sani, & Shamikula, E. (2019, November 28). Human Capital definition and importance. Retrieved February 3, 2020, from https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/26076/economics/human-capital-definition-and-importance/

Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2012). Poor economics: barefoot hedge-fund managers, Diy doctors and the surprising truth about life on $1 a day. London: Penguin.

DW News. (2019, November 19). South Sudan: A Last Chance for Peace? DW News. Retrieved February 3, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x_lXeyYuOnk

Peralta, E. (2017, July 3). Why is there conflict in South Sudan? | Let’s Talk | NPR. Retrieved February 3, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IZ9WmKA964o

Radelet, S. C. (2010). Emerging Africa: how 17 countries are leading the way. Washington, D.C.: Center for Global Development.

South Sudan . (n.d.). Retrieved February 3, 2020, from https://data.worldbank.org/country/south-sudan