Jacqueline Novogratz considers poverty a question of freedom and choice, or the lack thereof. She claims that to look at it objectively, you have to look at income as only one variable. Jacqueline’s message in the TED Talk is to convey that when the system is broken, that’s the time for the people to come up with their own ways to make their lives satisfactory considering their situation, with Jane, the tailor from the broken shack village outside of Nairobi as her example.

I watched and rewatched Rutger Bregman’s Poverty isn’t a lack of character; it’s a lack of cash Talk. He claims that the way to eradicate poverty is with a basic income guarantee. Which is kind of a different take on the subject completely, but they’re worth comparing. Novogratz’s idea of solving poverty comes by changing the outlook. It’s mostly about finding satisfaction with less, in terms of monetary value, but coming to peace and finding all the positives in her situation, such as pride in her work and love in her family. This required some charity money, but it also required work on her end to show that she was worthy of charity (which is a questionable concept, but is clear here that it worked especially well for her situation). Bregman’s theory is a bit more pragmatic, but doesn’t flush out enough ideas to be considered the most solid plan. But this is a 15-minute TED Talk, not a full plan of action. It seems that his methodology to eliminate poverty is to re-prioritize where our money goes so we can put the impoverished first. He mentioned abolishing the jobs of bureaucrats and just giving all their money to those who need it, because people being poor costs this country billions and billions of dollars every year (which I wish he would have elaborated on more). He had proof of this working in a few different communities, but never on a national level, which I believe is where the method gets tricky. But I don’t dislike the idea and don’t care particularly much about where money is reallocated to in order to make lives better.

I believe the solution lies in using bits and pieces from both of these ideas, as well as hearing out many more individuals from different wealth statuses in forming a plan that works. That said, I value Jacqueline’s idea more because all too often, regardless of wealth, people are rarely satisfied with the lives they lead and a change in attitude needs to come first. But, even if everybody in the world adopted this viewpoint, chaotic tragedies and misfortune and poverty itself still permeate the lives of too many people to find pride and spiritual fortune so easily.

On another note, the Sustainable Development Goals are a series of goals written by the United Nations that are intended to better every community on the planet. Each one contributes to an idea that betters the world by ensuring that every person is basically okay. They try to include all different ways to help society such as: Quality education, gender equality, no hunger, and teamwork. Whether it’s social justice or physical needs of the citizens of the earth, SDGs just try to eliminate all problems for all people. Neoliberalism seems, to me, to be the attempt to achieve these goals by cooperating with other nations to redistribute money equally among all countries in order to attain some equilibrium cash-wise. This all of course, is supposed to run through IMF and the World Bank.

In regards to John McArthur’s accused “Players on the Bench”, he’s referring largely to the United States, mostly under the Bush administration, but Obama holds some blame too, and the World Bank for not doing enough to eradicate poverty in struggling countries. World Bank, as the pillar for wealth distribution in, well, the world it should have played a much bigger part in fulfilling the Millenium Development goals, when they didn’t help poorer nations assess financial gaps or letting them know when it looked like there was another financial gap. The U.S. missed out mostly in the beginning by not following through on promises to increase world aid. By the time Obama was in office, it was practically too late to achieve the goals.

It seems that the 2005 article wanted to highlight all the ways we could be helping impoverished countries while recognizing the potential drawbacks. There’s a lot of variables that come with offering money. The people need to be in the right mindset, as to the bureaucrats. And the problem lies further in how much trust comes from those who dedicate the monetary offer.

In How Poverty Ends, Duflo and Banerjee spend ten pages discussing just what leads to fast economic growth. The end result is that it’s impossible to pinpoint one thing. It has to be a mix of smart decisions and good timing for the world of business. But what we are sure of is that improving quality of life by treating Malaria or AIDS for example can lead to further success for the country because the larger problems have been taken care of. I think that’s a really valuable insight. Good often follows good, and though economic growth may not be the direct outcome of lowering the amount of infant deaths, it’s most likely that the lives of the citizens has nowhere to go but up after that. I thought this text was worth reading, because it’s true that we can’t point to any one factor that leads to GDP growth, but we can look at factors that lead to better living situations for the people and go from there.

References:

Novogratz, J. (n.d.). An escape from poverty. Retrieved January 28, 2020, from https://www.ted.com/talks/jacqueline_novogratz_an_escape_from_poverty?language=en

Bregman, R. (n.d.). Poverty isn’t a lack of character; it’s a lack of cash. Retrieved January 28, 2020, from https://www.ted.com/talks/rutger_bregman_poverty_isn_t_a_lack_of_character_it_s_a_lack_of_cash?language=en

About the Sustainable Development Goals – United Nations Sustainable Development. (n.d.). Retrieved January 28, 2020, from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

McArthur, J. W. (2013, December 6). Own the Goals. Retrieved January 28, 2020, from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2013-03-01/own-goals

Birdsall, N., Rodrik, D., & Subramanian, A. (2015, September 15). How to Help Poor Countries. Retrieved January 28, 2020, from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2005-07-01/how-help-poor-countries

Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2019, December 11). How Poverty Ends. Retrieved January 28, 2020, from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2019-12-03/how-poverty-ends?utm_source=facebook_posts

Post #2: South Sudan’s Growth; Relative to That of Emerging African Nations

There’s a few factors that have been strongly contributing to Africa’s economic, humanitarian, and self-sustaining growth in the last couple decades. For example, the governments of a number of countries are becoming more democratic and reliable in terms of how much trust the citizens of each nation have in their leaders (These nations including Ghana, Botswana, Mozambique, Cape Verde, and a cluster of others). Another couple examples are the inundation of more reasonable economic policies, thanks largely in part to Nelson Mandela in the ’90s ending apartheid and uniting South Africa, which helped a number of businesses build the trust required to expand and help fuel domestic growth, as well as the large subtraction of debt from many of these nations. With fewer countries owing money to each other, tensions were lowered and they were excited to build a future together without the burden of wondering whether or not potential allies would be a mistake to invest in. In the wake of a technological revolution, you could find a cell phone in the hands of most citizens of these emerging countries as well, and with that comes even more opportunity for growth. They give healthcare workers a chance to spread important news of potential outbreaks or studies in different areas. The new technology has opened up the doors for jobs as coders and data entry careers, and it removed barriers for those located in different parts of the country or continent. People can now get to know and understand each other with fewer preconceived notions of places that they previously didn’t associate with (not in all cases but some) (Emerging Africa: how 17 countries are leading the way).

Plenty of countries are coming out from under the weight of poverty and helping their inhabitants the chance to live life without fear of hunger or safety, and it’s really exciting to learn about. Some countries on the other hand don’t have that same luxury as of late. My chosen country to research, South Sudan, is not in the same boat as these prospering lands.

South Sudan, as most are aware, has been in the throws of civil war and rebellion for the last five years or so, beginning with, as I’ve read/watched, the secession of themselves from Sudan, the now separate entity. In the search for freedom of religion and one’s own belief, new tensions quickly arose between the president and VP of the newly established country, when the president accused the VP of a sort of treason. President Kiir being a member of one tribe and Vice President Machar being of another, this rapidly promoted a sense of hostility between tribes. This resulted in a rebel uprising in the newly developed society and has since sent them down the path of civil war, which they broke away from Sudan to eradicate for themselves in the first place (Why is there conflict in South Sudan? | Let’s Talk | NPR).

In the time since civil war in 2013, over 400,000 South Sudanese citizens have been killed, over 4 million have fled the country, and plenty within the country have been displaced. Now as tensions have lowered a bit, President Kiir and former Veep Machar have signed a treaty uniting the two militaries as one, but a lack of funding has kept them from moving forward. As a result, the lack of finalization of their plans to come together has kept the country from developing further. They still rely heavily on aid, but with the constant expansion of deadlines is making countries like the U.S. hesitant to continue giving relief if the light at the end of the tunnel is still not in sight (South Sudan: A Last Chance for Peace? DW News).

As it goes, the factors that were helping nations like Ghana and Mozambique prosper are nowhere to be found in South Sudan. After all the fighting that it took for them to secede in the first place, then further violence in their newly established home, there’s still little trust to be had in their government, technology can’t be afforded by those who don’t even have access to a reliable food source, and the country hasn’t yet figured out an economic plan that unites the people when they can’t come to guaranteed peace in the first place.

It’s entirely possible to be trapped in poverty. Trapped doesn’t have to imply permanence, but it does promote fear of permanence. There are hundreds of countries around the world that have been stuck in a state of instability for decades, or centuries in some cases (Poor economics: barefoot hedge-fund managers, Diy doctors and the surprising truth about life on $1 a day). But, as previously stated, it’s possible to come out of. With some well-placed help and under the right circumstances, countries can be pulled out of debt. In the cases of Botswana and Ghana, it starts with democracy. South Sudan has elected officials, but they don’t have trust for them to end the fight they continue to have with themselves over topics as simple as “This is where I harvest!” “No! This is where my cows graze!” Tribalism, as it stands, is still an issue that promotes violence against other tribes (not unlike patriotism). And within the governed vs. the rebels, the land of rebels is being left out of government-run health and food programs, which only escalates tensions.

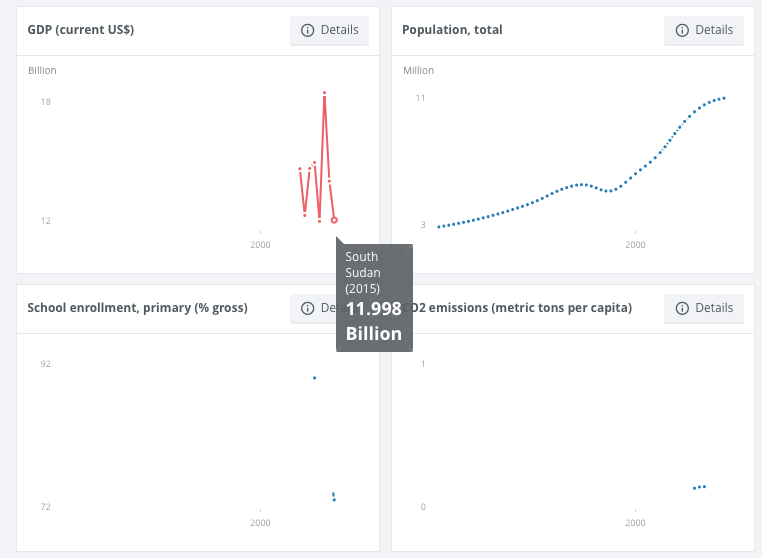

The World Bank website offers some questionable information on South Sudan. It claims that the population of the country has only gone up since 1994 until 2018, where it stops. This doesn’t fall in line with the numbers reported previously regarding all the deaths and and the 4 million emmigrants of the country. The charts regarding CO2 emissions, school enrollment, GNI per capita, and GDP haven’t been updated since 2015, which isn’t a good sign. And the life expectancy has only risen since 1960, which doesn’t seem to add up either, given the famine. I also assume that the stats about the country before the country’s founding in 2011 just speaks of the area before it became its own unit. The Gross Domestic Product dropped critically after 2013 when rebellion began to take place and hasn’t been reported to come up since, at least according to World Bank. This goes to show that the Sustainable Development Goals aren’t being met even a little bit since the country is no longer in a state of war, but is still more or less war-torn. Poverty headcount increased by nearly 18% between 2016 and 2018. But thankfully CO2 emissions only rose by .01% in the last year that they collected data. (Year in Review: 2017 in 12 Charts), (https://data.worldbank.org/country/south-sudan).

It’s hard to report that there’s no capacity for human capital in South Sudan (Human Capital definition and importance), but the statistics look bleak. To assume that the citizens of the country aren’t fit to work based on their lack of formal education and creativity given their current situation. There’s not a lot of job security in a land with no security at all, so it human capital in the nation looks almost nonexistent on paper. South Sudan’s is also not taken into account on many lists outside that of the world bank. I assume this is due to the lack of organization necessary to collect such data accurately. But I suppose my question is: Can human capital be calculated by stats such as these? In a country that doesn’t hold opportunity for capital, does that mean that the people aren’t capable of it? Or is it that its leaders have to organize themselves before the people are able to help the nation capitalize? And is it unethical for organizations like the IMF to pay no mind nations locked in poverty like this?

Year in Review: 2017 in 12 Charts. (n.d.). Retrieved February 3, 2020, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2017/12/15/year-in-review-2017-in-12-charts

Pettinger, T., Sani, & Shamikula, E. (2019, November 28). Human Capital definition and importance. Retrieved February 3, 2020, from https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/26076/economics/human-capital-definition-and-importance/

Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2012). Poor economics: barefoot hedge-fund managers, Diy doctors and the surprising truth about life on $1 a day. London: Penguin.

DW News. (2019, November 19). South Sudan: A Last Chance for Peace? DW News. Retrieved February 3, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x_lXeyYuOnk

Peralta, E. (2017, July 3). Why is there conflict in South Sudan? | Let’s Talk | NPR. Retrieved February 3, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IZ9WmKA964o

Radelet, S. C. (2010). Emerging Africa: how 17 countries are leading the way. Washington, D.C.: Center for Global Development.

South Sudan . (n.d.). Retrieved February 3, 2020, from https://data.worldbank.org/country/south-sudan

Post #3

The “Big Man”, as briefly described by Radelet in chapter 3 of Emerging Africa, refers to the dictators of the countries yet to emerge in Africa around the time of the late 1980s before democracy had risen in popularity. “Big Man” was a state of being as well as a mindset for those who were in charge. He was more concerned with the maintenance and growth of his own power versus the well-being of his people and the problems they had with their respected countries’ state of affairs.

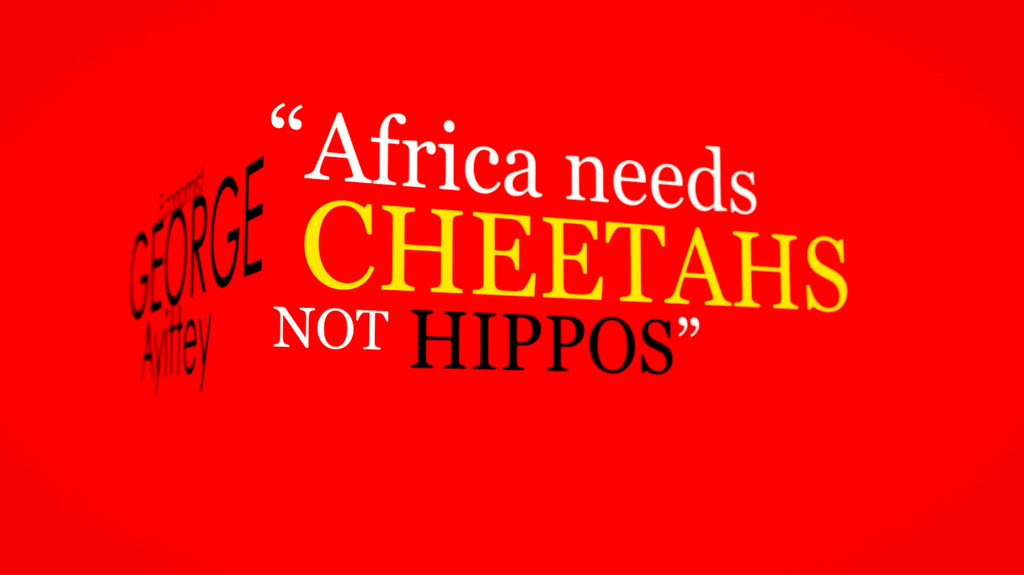

The “Cheetah Generation” is considered the generation that seeks and works toward progress in their countries. The Cheetahs want see Africa for its potential and promote change in their governments. They want transparency and honesty from their rulers, not corruption, greed, and content with a failing system. “The cheetah generation means many things, but five stand out: ideas, technology, entrepreneurship, market power, and the push for good governance and accountability.” (Radelet).

The “Hippo Generation” on the other hand is the party that doesn’t mind the state of affairs that plagues the economy and lack of democracy of the country. Hippos are unbothered by a failing system because they have the power to work around it. Hippos are more often than not, the ruling class, governing the country with outdated methods. “They proved to be far more proficient at fighting against the colonial government than they were at running their own. The leaders consolidated power in their own hands, weakened mechanisms for accountability and transparency and hung on in office for far too long” (Radelet).

I think Radelet’s views of the Internet and Mobile explosion in Africa is really justified. Africa’s catching up to the rest of the modern world in terms of disposable information and available technology. In terms of sustainability, it doesn’t come off as any less sustainable than what we’re working with over here. Radelet doesn’t go into detail on the amount of factories or industrialization. And from a quick Google search, it looks like the level of industrialization is growing, but not to the point of environmental harm and pollution produced in the U.S., Brazil, or industrialized Asia. Business and networking is growing for the 17 African countries coming out of the dark ages. The installation and maintenance of fiber optic lines on land or under the sea has created hundreds of new jobs across the continent. Farmers can update buyers on the state of their crops and through services like TradeNet, they have instant access to knowledge of who they’re marketing with. Village phone operating is a viable career to plenty of local work-seekers (women in large part) who couldn’t read or write ten years ago, but are now tech-competent and contributing to the community while making a steady wage! Radelet’s excitement for the tech boom in modernized Africa seems completely justified.

One challenge that had to be overcome at the time the book was written was the cost of web service, which was “20-40 times higher” than we paid in the U.S at the time. But Radelet predicted that prices would soon drop, which is taking longer than expected. So much so that Africans have formed the Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4AI). But apart from that, challenges only seem to be disappearing faster. Issues like banking and money transfers have been solved through mobile phone usage so the costs of wiring money through third party sources like Western Union are deteriorating. People can move funds around with much greater ease and security than in years past. The most prominent problems that come with the technology are fake news and defamation of politicians or other public figures. But services have sprouted to basically fact check and verify the validity of such claims. Things really do seem to be looking up.

As for my selected country to research throughout this course, South Sudan hasn’t upgraded in the same way the 17 emerging nations Radelet speaks of. But nonetheless, there are heroes to be spoken for in their communities. South Sudan is slower to the industrial punch, but isn’t devoid of technology by any means. One man who makes use of what the country has is Elias Tande, a radio presenter. Elias spreads good word throughout his community and speaks for advocacy and good governance. He uses the media outlet at his disposal to build peace by keeping his listeners informed. In a land that doesn’t have the same access to information as much of the world, it’s easy to be misinformed or to make presumptions of what the other side (be it rebels or tribalists) feels or how they act. Tande attempts to bring clarity to his people. He carries a lot of weight at the station as well, as a concept developer, producer, and host of the radio show. In an interview with Strathmore University, he states “But you see the laws are there – yes – but then our cultures are always there. And the way you bring in the law into the lives of people within the cultural context may affect them in the other way around. So it really taught me so much on how to get into the cultural context and try to change the mindset to a positive one.” This being in the context of rebels versus tribalists and how to keep each of their cultures sacred without breaking laws and causing violence in the community until the government can come to a satisfactory consensus for all. I would by all means consider Elias Tande a cheetah.

Democracy can’t be defined by any one, concrete factor. It’s a series of issues that considers how the people of the nation are treated and governed, and how those who govern do their jobs. It’s determined by civil liberties, political rights, opportunities as citizens, individual freedoms, and other terms that describe just how free the people are. According to Freedom House, South Sudan is ranked among the lowest for all of these issues. As a country broken into pieces by civil war, its electoral process possesses little to no room for organization. The last election, five years ago was postponed thanks to war among tribes. And the official president originally elected in 2010 basically has chief authority over all the land. He can fire any staff member at will and cannot be impeached. The people have little to no right to oppose. Its aggregate freedom score, again from Freedom House, is 2/100. Its state fragility index according to Systematicpeace.org is “extreme”.

Thankfully, YALI (Young African Leaders Initiative) is at least a little active in South Sudan. There’s a few standout members that are making changes step-by-step in various communities. One example is Abraham Bakuenyin, an alumni of the Regional Leadership Center East Africa. He’s completed his share of YALI Network online courses and has spent much time “engaged with training and advocating for Women’s Rights, Human Rights, and encouraging meaningful youth participation towards peace and nation building.” He’s just one among a few members working with the citizens of South Sudan to help build communities and unite people in the pursuit of peace and understanding. (YALI.state.gov).

In regards to the second part of the blog post, some effective health investments include: bed nets, IV solutes (salt and sugar), chlorine and bleach for mass water purification, immunizing drugs (a vast list of inexpensive meds and vaccines). And certainly the most important health investment for every one of these communities trapped in poverty is education. These people have potential access to bed nets and water purification if they would just put up a little bit of money to invest in such products, but evidence shows that they often don’t, even if they have the money. Duflo & Banerjee claim that the poor seem to spend their money on expensive cures rather than cheap prevention in most cases. Education as well as destigmatization. Even the poor look down on free public healthcare rather than private care. Another necessity is qualified doctors. All across India are “Bengali Doctors” with some to no training. Some are foolishly confident, some are reasonably aware of their skills or lack thereof. Regardless, they still don’t hesitate to practice medicine in whatever village they settle in.

Another issue is the government health system. The rate of absent healthcare providers funded by the government is entirely too high. Bangladesh, Ecuador, India, Indonesia, Peru, and Uganda clocked in at an average absentee rate of 35%. Duflo and Banerjee go on to claim that even when the doctors and nurses were present, they didn’t do a satisfactory job (satisfactory by the lowest of standards). They would under-analyze the patient, then over provide with various medications after learning damn near nothing about the patient’s ailment. So as it turns out, it’s not even that the poor are misjudging government-funded healthcare. It kind of deserves to be looked down upon. Add better doctors and higher healthcare standards by the government to the list of things to invest in. BUT! Even when they performed a test to provide communities with proper healthcare initiatives like free vaccines, the rate of those who went fully immunized only rose by 11%! So what’s to blame? Is it the people for not informing themselves when the resources and advertisements for such resources are all around?

Some of this goes back to ignorance. Many people don’t use certain remedies because there are faith-based aversions to such remedies as immunizations, or, in some cases, just eating rice. The case may be that what people need is to be constantly reminded of what they have at their disposal. No amount of aid, be it monetary or the actual, physical relief to their problems if those who need the aid are still in the dark about the wonders of modern medicine and preventive products. We see the same thing in developed countries. Ignorance and lack of initiative to care for one’s self. We should just be thankful that our surroundings aren’t as dire and that this doesn’t apply to the majority so vastly. (Duflo & Banerjee).

South Sudan. (2019, May 20). Retrieved February 11, 2020, from https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/south-sudan

Center for Systemic Peace. (2018). Retrieved February 11, 2020, from http://www.systemicpeace.org/conflicttrends.html

Country of the Week: South Sudan | YALI. (2018, October 16). Retrieved February 11, 2020, from https://yali.state.gov/country-of-the-week-south-sudan/

Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2012). Poor economics: a radical rethinking of the way to fight global poverty. New York: PublicAffairs.

Radelet, S. C. (2010). Emerging Africa: how 17 countries are leading the way. Washington, D.C.: Center for Global Development.

Strathmore University (2018, December 10). The everyday heroes of South Sudan. Retrieved February 11, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q3KR9pXl8xk

Post #4: Loans in Africa?

I’m not gonna start off this entry by pretending to understand the business of loans in Africa from sources that I’m still not entirely sure of the origin of. There were a lot of acronyms that I feel I never got a definition of and I just kind of accepted it. I just now googled what an MFI is and it seems to be a MicroFinance Institution. Seems about right. I honestly processed so little of the information I read because I just do not understand the complexities that go into why people of low-income Asia would or wouldn’t take out a loan when they stay below the poverty line without the additional help. I know Duflo and Banerjee did their best to explain it to me but after 70 pages worth of information that I had what felt like only a little context beforehand, I wasn’t willing to go back and reread it. Please give us less information to research, or, at least, give us more specific page numbers so that we can find the necessary evidence without sinking two hours into skimming pages before discovering the data necessary to complete this blog post.

Duflo and Banerjee in chapters 8 and 9 spend a lot of time talking about things while not alluding to why they’re talking to them. That’s what it felt like anyway. I saw the terms “Microcredits” and “Microloans” a few times, but not enough to know that that’s what they were talking about, so I’m assuming they were because that’s what this post is supposed to be about and those were two of the chapters assigned. It seems the rate of return for many business is too risky for many small firm owners to confidently go into considering the loans that would need paid off and the work necessary to build their businesses. And after you put in the amount of work necessary to maintain your new and improved business, the amount of money you’re now making may not be worth the trouble of taking that loan out in the first place, regardless of the size.

That said, there’s plenty of examples of businesses working out successfully after that loan has been put to good use. There’s the lady that went all-in and bought a sewing machine versus some saris to resell, then taught a bunch of local girls how to use it, then they got their parents to buy them their own machines, then began a business tailoring clothes for everybody around. The issue is that not every business has the money to even invest in a larger loan that would put them above the much-coveted S-curve that leads to marginally higher profits.

On top of that, there’s a pretty high amount business owners that aren’t interested in even taking out a loan in the first place. My favorite example of which is the cattle farmer that has enough cows to provide for his wife and three children. He could buy more cattle with a small loan and turn over notably higher profits if he would, but he doesn’t have the land necessary to support the extra cattle. They wouldn’t have the necessary amount of acreage to graze. And he’s not particularly interested in buying more land for his venture in capital because he makes enough money as is to provide for his family. I just really like the way he looks at things.

Microcredit transactions in South Sudan seem to be a particularly huge disaster thanks to the amount of hope people had going into the founding of the country in 2011 and the civil war that broke in 2012, according to Chrystal Murphy’s Microcredit Meltdown. Six years after takeoff of the loans that went into the funding the country’s foundation, some 80,000 participants were left basically fucked before the microcredit industry in the world’s newest country before it was even fully constructed.

“Yet the over promising and under-delivering commercial microcredit was not isolated to South Sudan or even post-conflict settings. The Juba microcredit story is an instance of the broader global shift toward the commercial microcredit model. Initiated to get badly needed capital into the hands of poor people, instead the focus became sustaining a lending program.” states Murphy’s abstract on her website. So it seems there still seems to be a larger sense of capitalizing on those who need it versus the sense of charity and hope that their money finds its way back, which would certainly be a more helpful outlook in a situation this bleak.

I have, however, found a charity that goes toward micro financing women of South Sudan’s Magwi County, which asks for $30 donations to train the 200 local women in business and management.These being the women who recently returned home after being displaced for some years. W4.org states as follows:

“Upon completion of these courses, the women form small groups of approximately 20 women borrowers. These groups hold weekly meetings and are a crucial component of the project; they serve both to provide support and solidarity for the women in their small business endeavors and to help ensure loan repayments, thanks to borrowers’ mutual oversight.

Each woman is provided with an annual microloan of $125 and makes monthly loan repayments of $10.42 (a 20% interest rate funds the complementary training and a revolving loan fund to provide loans for more women). The women use their loans to start small businesses such as bee, poultry and vegetable farms, grocery shops, handicrafts, or tailoring boutiques.

<https://www.w4.org/en/project/empower-women-returnees-south-sudan-with-microloans/>

There are a decent amount of funds and charities made to micro finance citizens of South Sudan even after the disaster that was/still kind of is civil war. Most of which don’t seem to have released information about how the efforts are going, but instead listing the goals of such efforts. Although, plenty of operations such as the Kiva fund for instance, began in 2011 and have since closed their doors, sadly accepting the fact that “all 118 loans worth $26,279 have been defaulted as of January 2017, and the partnership is now closed.” It makes sense that a sizable amount of the funds made to help the citizens build their own businesses are now charity-based. I agree with the limits given that the country remains in a state of instability. Money isn’t the answer to their problems right now when the government is still fighting itself.

The Mobarak article doesn’t seem unreasonable. It’s certainly not convenient for the people of Malawi, whose urban areas are also riddled with unemployment. As for people of Nepal, they can seasonally move to India, where wages are reportedly much higher (which seems confusing based on everything I’ve read and heard about the large poverty rates in India, but I’m probably not taking every factor into account for that). I think it’s solid idea for those who it actually helps. And in places like Ghana and Nigeria, it looks really promising while not having to make too many sacrifices. In South Sudan on the other hand, the cities are just about as poor as the countries if not more so. So migration within the country isn’t much of an option for better job opportunities, except for perhaps the southwest side that neighbors Kenya, which does a little better in terms of human capital.

But South Sudan has a lot of arable land and water sources that haven’t been tapped yet. Plus the Nile runs right through it, so there’s plenty of fertile land especially in the south upper stretch of the river (right in the middle of the country). And according to one study done primarily by the WPF (the Odero/Hollema pdf document), they also have access to an abundance of cattle and fisheries. If the nation could find peace among themselves, they would certainly emerge at a quicker rate than most. But until then, it seems that the potential the land has won’t be taken advantage of.

As for the last article about all the wealth being stolen from Africa, I don’t think there’s anything to agree or disagree with. Africa’s insecurity has been taken advantage of for years and everything here seems like concrete facts. If there’s wealth flowing out of Africa (which there seems to be) I’d say they deserve justice more than any other place in the world given how the people there have lived for the last few centuries versus everywhere else. I have no evidence that states anything that disagrees with the information provided by Al Jazeera. I wouldn’t want to disagree anyway.

Part B of this discussion leaves us with the last chapter of the book and what side to take: Easterly’s conservative approach or Sachs’s more liberal one. As a leftist myself, I love the idea of repurposing the money we give toward services like the military and the income of domestic bureaucrats and directing it those who really need it both in and out of the country. But it stands that an unstable country is unstable and untrustworthy. This doesn’t come from a place of spite toward any country with a collapsing government, but I wouldn’t give a homeless person more than a couple dollar bills that I have on my person. And if I don’t have singles, I’ll give them a cigarette. But it’s foolish to invest in a country, especially like South Sudan before their government is even intact. At least monetarily. If we had a president like Carter in the White House, willing to go to the middle of Africa to negotiate with the heads of the government, Camp David-style, I’d be all-in and Trump might actually get my vote for reelection if he showed that kind of interest in countries that need help. But to simply throw money and poorly-run social programs at a nation that needs to find peace for themselves I think is to manage money poorly. Once South Sudan helps itself, it will be more than worthy to receive help from anywhere else.

Gertz and Kharas in The Road to Ending Poverty do list South Sudan as one of the “Severely Off-Track Countries”. It’s obvious as to why, I’ve repeated that it’s plagued with civil war between tribes a dozen times through these blogs. This is the obligatory answer to that question.

References:

Dearden, N. (2017, May 24). Africa is not poor, we are stealing its wealth. Retrieved February 17, 2020, from https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2017/05/africa-poor-stealing-wealth-170524063731884.html

Empower women returnees in South Sudan with microloans. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2020, from https://www.w4.org/en/project/empower-women-returnees-south-sudan-with-microloans/

Field Partner. (2017, January 12). Retrieved February 17, 2020, from https://www.kiva.org/about/where-kiva-works/partners/206

Gertz, G., & Kharas, H. (2018, February 13). The road to ending poverty runs through 31 severely off track countries. Retrieved February 18, 2020, from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2018/02/13/the-road-to-ending-poverty-runs-through-31-severely-off-track-countries/

Microcredit Meltdown: The Rise and Fall of South Sudan’s Post-conflict Microcredit Sector. (n.d.). Retrieved February 17, 2020, from https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781498577380/Microcredit-Meltdown-The-Rise-and-Fall-of-South-Sudan’s-Post-conflict-Microcredit-Sector

Mobarak, A. M. (2019, July 4). Instead of Bringing Jobs to the People, Bring the People to the Jobs. Retrieved February 17, 2020, from https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/07/04/bring-the-people-to-the-jobs-seasonal-hunger-migration-bangladesh/

Odero, A., & Hollema, S. (2012). PDF. Italy.

Post #5: Defining Geopolitics & the Value of History

I’ve never given much thought to the true definition of geopolitics. I’ve taken the name at face value and kind of put two and two together. I assumed it was little more than the political relationship between different countries, states, and territories. The way Dugin defines that term, isn’t far off from mine, it just goes deeper.

Dugin makes the claim that “Space in geopolitics plays the same role as time for history.” He says that it’s about the interactions and relations between spaces, peoples, cultures and economics. It doesn’t boil down to one central issue or theme, but it’s largely about the way that different territories perceive one another. He notes the value of having a “True North” and “True South”, because people can see themselves as further North or further South without any debate. There can be some heat or tension when referring to the locations of countries incorrectly, not unlike the way that people of Latin decent are often liable to get upset by mistaking them for originating from another South or Central American country. It’s about those little relationships between different cultures and how we’re all more or less different and the same.

What makes geopolitical relations so complex is that so few citizens of the world are truly good at negotiating and discussing in that field. You’d have to be extremely familiar with every culture on a grand scale to figure a way to achieve peace between all states and peoples of even one continent. Africa’s a great example, since we’ve spent a lot of time researching and discussing it these last few weeks. What’s good for some tribes isn’t necessarily good for others. One may think that every individual could look at a sustainable development goal pragmatically and say “Yes, good idea.” But then comes different politics and beliefs and religious restraints and arguments of how to execute it more practically in the eyes of one’s own deity rather than their neighboring civilization. It’s little indiscretions like that which cause tension between peoples and a lack of global solutions. South Sudan may be much better off if it’s communities had a greater understanding of one another so they could work toward peace quicker.

When I searched for additional information on Middle Eastern politics by way of TEDtalks, I couldn’t help but notice the way they were organized. The top 15 results were three comedy sets discussing politics of the region, two of which were by Maz Jobrani, five were Middle Eastern feminist speaker profiles, only three were serious discussions varying on topic but all themed around very sensitive issues, and then another profile, a playlist of 9 videos, and two profiles for white guys who discuss how to make peace. As a comedian, I was naturally drawn to Maz Jobrani.

Maz did a six-and-a-half minute set on the differences and similarities between the people of the Middle East. He went over the differences in the amount of kisses people of different cultures give when they greet one another, and the least threatening way to speak when they board an American airline, as not to arouse suspicion. The set wasn’t necessarily deep, but I couldn’t help but take note on how diverse his crowd was in Doha, Qatar. It was, in every sense, wholesome how all the different ways of life in the audience were willing to laugh at what they had in common as well as their differences. It was clear that Maz’s end goal with his speech wasn’t to solve issues on a geopolitical level, but to simply unite the spectators with jokes about how they all live. It was fun to watch them all connect like that, and there’s certainly something to be said for the way comedy brings people together. This blog post, however, is likely not the place because it would be twice as long if I got into it.

Kinzer makes connections between Iran and the U.S.’s similarities. Both have a strong value of democracy, as does Turkey, and they share many similar goals in terms of oil production and the desire to govern themselves without outside decree. They’ve shared similar enemies: The Soviet Union, Afghanistan’s Taliban, and Saddam’s Iraq. America has seen the end for all three of these global nemeses, thanks in part to Iran. Both countries would also like to see Iraq stabilize and be ruled by the peaceful majority, I.E. the Shia and to extinguish ISIL (this from belfercenter.org). From the way we govern, to our international goals, The U.S. and Iran many have more in common than either country is willing to believe.

Kinzer spends the majority of Chapter 1 going over a long relationship in the Middle East between Turkey, Persia, Great Britain, and the United States, and the Soviet Union. He goes over a lengthy story of Persia’s struggle for peace and democracy and how it was taken away from them just when things were looking up. The conflict being over, who woulda guessed? Oil, and Churchill’s perception of what-was-yet-to-be-Iran being of dire importance to the UK if it wanted to remain a world power. It took meddling between Great Britain and Russia take the peace that Persia had finally achieved and remove it for the sake of greed. It was upsetting to listen to.

The value that the story holds however, is one that you would think would ring like a bell in the hearts of Americans. It’s a tale of wanting more for one’s country, and for its people to be happy and content with what they call home. You’d think that more Americans would hear that and sympathize with the citizens of Persia, because we too were once held back by the colonial hand of the British. And it goes to show just how much we have in common with them. Our goals fall under the same category. It’s little more than backgrounds, traditions, and preferred executions that show our differences.

That’s the importance of history. When you look back at a nation’s past, you can find all sorts of common ground and shared interests to celebrate together. That’s the soil that you plant the seed of a new relationship in, and there’s nowhere to go from there but up, just as soon as one can make attempt to acknowledge each other’s differences, work with them, and come to a communitive understanding, rather than argue and only see dissimilarity. To make an attempt to learn the geopolitics of a region and work in tandem with them is the first step toward peace.

References:

Kinzer, S. (2011). Reset: Iran, Turkey, and Americas future. New York: St. Martins Griffin

Geopolitics: Theories, Concepts, Schools, and Debates. (2019, January 2). Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://www.geopolitica.ru/en/article/geopolitics-theories-concepts-schools-and-debates

CaspianReport. (2019, January 22). Geopolitical analysis for 2019: Middle East. Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dpbAHiWrwmc

Allison, G. (2016, March). US and Iranian interests: Converging or Conflicting? Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://www.belfercenter.org/publication/us-and-iranian-interests-converging-or-conflicting

Jobrani, M. (2012, April). A Saudi, an Indian and an Iranian walk into a Qatari bar … Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://www.ted.com/talks/maz_jobrani_a_saudi_an_indian_and_an_iranian_walk_into_a_qatari_bar

middle east. (n.d.). Retrieved February 24, 2020, from https://www.ted.com/search?q=middle+east

Post #6: Oh My God, I’m So Conflicted

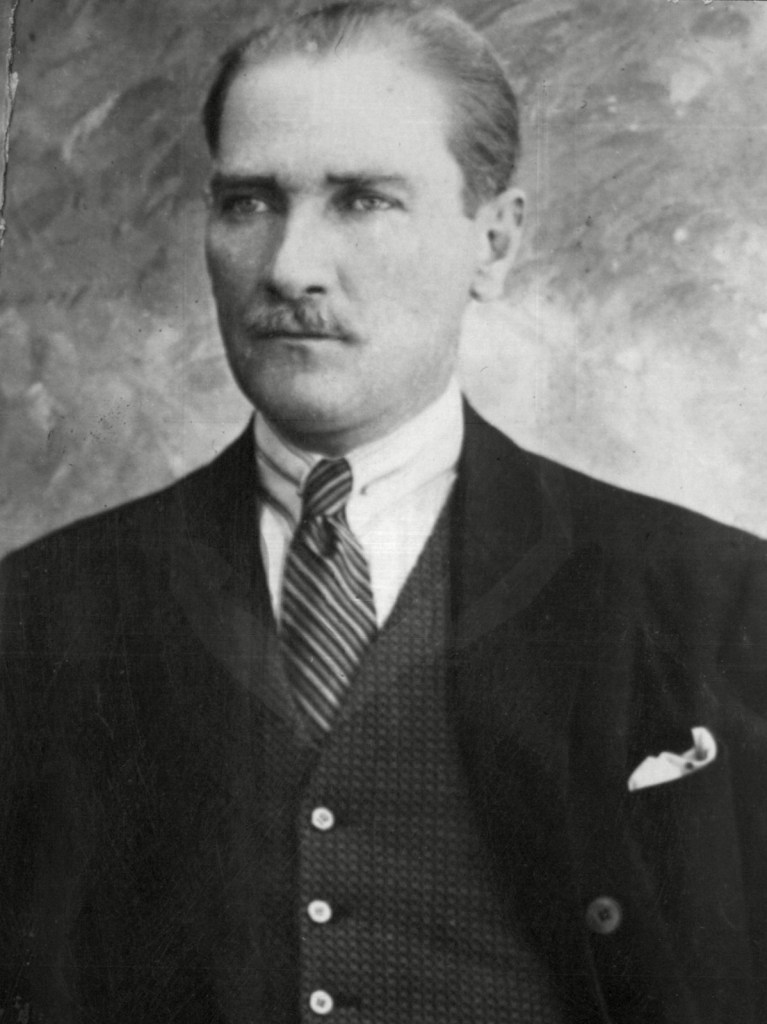

I don’t know if it was the content that I was consuming or just listening to the Kilner’s audiobook at 1.75x was what I needed to really get absorbed in this content, but this is the most captivated I’ve ever been by a reading for a writing intensive. Mustafa Kemal has one of the most polarizing biographies of any leader I’ve ever heard. To be so wrapped up in changing the ways of radical religious rule that he executed on the spot anybody who opposed him, in that of a similar fashion to the nation he was trying to set his own apart from was so crazy to hear. I was just cleaning my front yard and if anybody was spectating, they would’ve seen my eyes widen and jaw drop every eight seconds when I heard a new fact about his brilliant(?) lunacy(?).

The term secular modernity describes a civilization that is ruled by law. Not law that has been foretold to the people through ancient religious text, but that of which is conceived and implemented by modern governors of modern nations. I’m pretty sure it’s what most political systems today follow. Kemal wanted a country that was detached from the ways of traditional Shi’a Islamic rule and replaced with the western and European ideals that were current at the time. The way he achieved it was through means by which shocked me though. First of all, the audiobook I found on Audible numbers it’s chapters weirdly so I accidentally listened to the tail end of chapter 2 without realizing it, and I was floored by how Kemal lead Turkey to true independence, and then ruled over it with an iron fist. I also couldn’t get a read on Kemal for the longest time. He was described like a fearsome, fun-loving dictator that seemed to be so admired by his people even when he was showing signs of foolishness, weakness, and tyrancy. I couldn’t tell if he was a good or bad guy for the longest time. Even now I can’t tell how I feel about him. He sounds insane and the way he ruled and transformed Turkey so quickly without regard for how anybody felt about it is so conflicting. It’s completely admirable in many ways because he did, what I believe to be, the right thing: He took a nation whose growth seemed to be stunted by that of ancient Islamic law and did a complete 180 for the sake of freedom, prosperity, and secular dynamics. But in the process, his presidency mirrored a dictatorship because so many people weren’t in favor of it. And those who weren’t were quickly imprisoned or killed. But in the end, he advanced their society faster than it ever would have prospered under Shi’a rule and gave women the rights they deserved and turned it into a land of scholars and people who would one day sing his praises. It’s crazy to think about, but I think regardless of his methods, I’m a Kemal fan.

Iran played a different game that had a harder time adopting such secularity. They were a little slower to change and wanted to uphold some traditional Muslim ways. Kemal was radical, as to where Reza Shah didn’t feel inclined to remove religion from anybody’s way of life, rather than to take steps in modernizing the country for the sake of necessary change. He banned the chador from the work force for the sake of making women less restricted physically and imposed taxes on places of business that didn’t cater to both sexes equally (or at least closer to equally). He showed respect toward Jews and believed women should be educated and saw that the national railroad be built. He made progress happen in Iran. That said, though his newly imposed ideals were not as quick and radical as Kemal’s, it also preserved some unhelpful ruling methods, such as government monarchy, so that his son could later rule the country (which did not happen), and seemed almost as quick as Kemal was to exact power on anybody that defied his reign or new decrees through brutal force and executions.

Dodds states and restates the value of thinking critically in terms of geopolitics. This means to challenge any preconceived notion of a region or state and to thoughtfully acknowledge the nuances that are in the way of how any global politician or even citizen may think about a nation. There’s plenty of “Geographical facts”, as Dodds scoffs, that ignores plenty of geographical complexities. And thinking about any issues with a binary state of mind doesn’t help to solve any problems. It just categorizes problems and countries incorrectly and with lack of deep thought. A broad example Dodds uses is that we often perceive a nation as one singular entity and press the thoughts and opinions and needs of everybody from government official to blue collar employee to college student into one collective hive mind. Along with that comes the thoughtlessness that considers Paris all of France, while disregarding the needs of each individual community in the country. And in an ideal geopolitical landscape, we would be taking everything about the political environment and physical ecosystem of a space into consideration. We would think about not only how it would affect the elected officials of a region, but the animals and the terrain. We have to consider the country folk of the Middle East and not just the loud, upset bureaucrats in Tehran. And it won’t be until we take every factor of a place and a space into account that the world can come to a global understanding of itself. It requires work and research, conversation and debate but Dodds is absolutely correct when saying “It is essential to be geopolitical.

References:

Kinzer, S. (2011). Reset: Iran, Turkey, and Americas future. New York: St. Martins Griffin.

Dodds, K. (2014). Geopolitics: a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.